by Julia Flamingo

The Grand Dame of computer-assisted art, Vera Molnár, died on December 7th, 2023, just months before the centenary of her birth and the opening of the Pompidou exhibition last February 28th. Molnár dedicated 99 years to what we call Generative Art today—what most of us still don't even understand in 2024—and cemented her legacy as a pioneer in creating art using algorithms, codes, and machines.

Speak to the Eye [Parler à lœil] exhibition tells this chronological story on the 4th floor of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, bringing together representative artworks created in different decades in an elegant instalment. Born in Hungary, Vera Molnár trained in classical painting at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts and graduated as a professor of art history and aesthetics. Her earliest creations presented at the exhibition are 22 of her diaries, which reveal a very intimate perspective of how she could see geometric forms everywhere. A collection of drawings from 1946 presents landscapes as geometric abstractions: foliage became circles, and trunks of trees are simple lines.

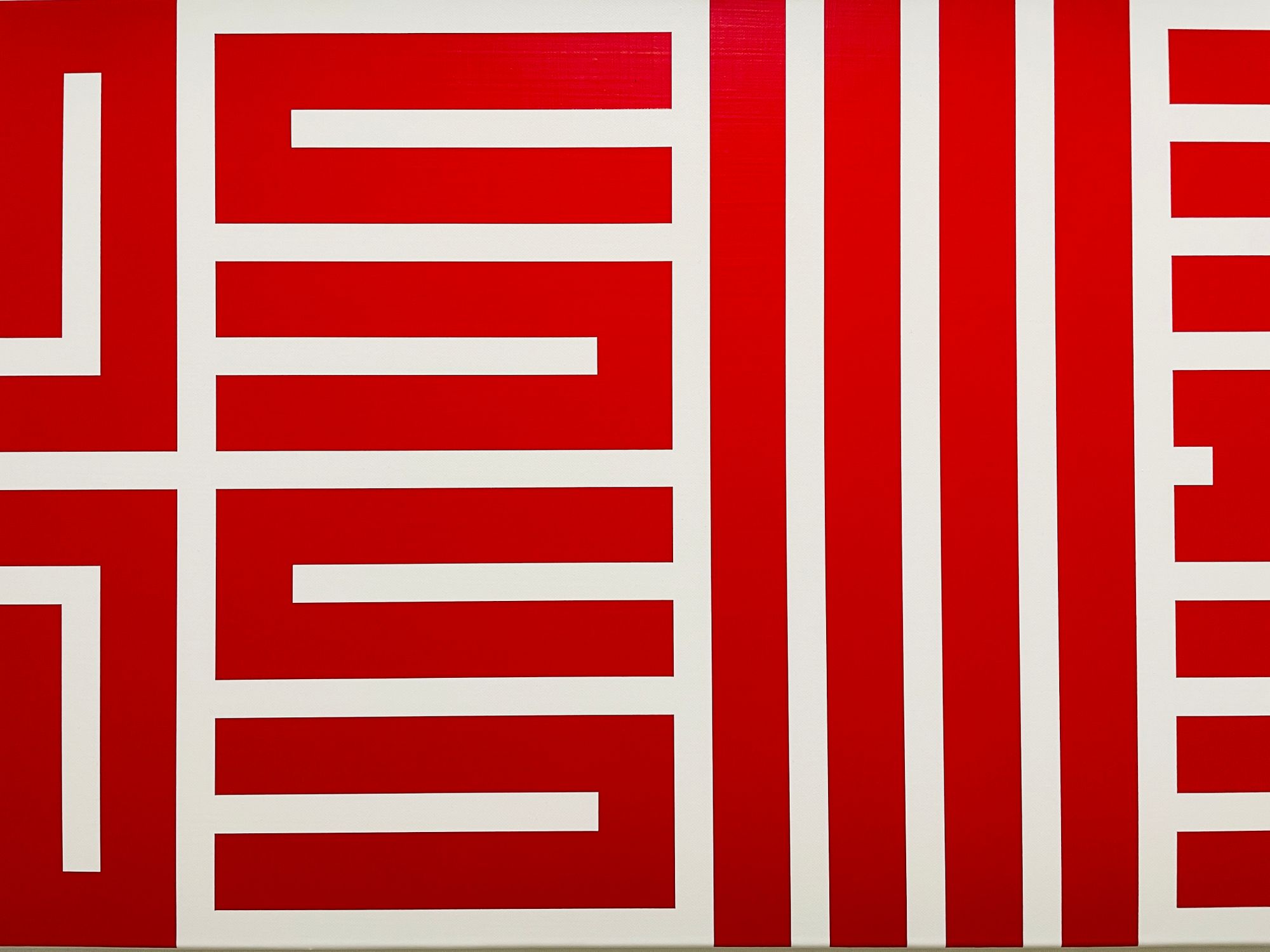

Paris is also the city where Molnár established her career. She moved with her husband, the scientist and sometimes collaborator François Molnár, in 1947. She then established fruitful relationships with celebrated artists like Sonia Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Victor Vasarely, François Morellet, Aurelie Nemours, and Max Bill. Although her geometric inclinations and optical effects are everywhere to be seen in the Pompidou exhibition, which could approximate her investigation of concrete artists, curator and art historian Vincent Baby defends the opposite in the exhibition's catalogue: "The artist remains one of the few representatives, along with François Morellet and Julije Knifer, of a certain form of anarcho-constructivism that unashamedly flirts with so-called conceptual art."

Indeed, Molnár was somewhere in between, as she often proclaimed: "I situate myself between the 'con': the conceptualists, the constructivists, and the computers." François Morellet, whom she met in 1957 through Jesús Rafael Soto, shared similar preoccupations in the desire for elementarism, minimalism, and systematic geometrizations. A "rigor in the investigation of pictorial possibilities from a reduced formal vocabulary led them to assimilate and then transcend the experiments of the Bauhaus, the De Stijl movement, and the Russian and Polish constructivists, making them evolve towards a radically original artistic approach," writes the author of the book.

However, as Vincent Baby defends, while the works by François Morellet are now well known and held in museums around the world, Vera Molnár's work is just starting to receive the recognition it deserves. Again, this is one more underrepresented woman artist whose pioneering practice wasn't acknowledged. She developed an in-depth understanding of the possibilities offered by emerging technologies and merged them with her extensive expertness in art history. A rare blend to find among artists working with the latest technologies until today. Better late than never, and in the wake of NFTs and Artificial Intelligence, she was included in the main exhibition of the Venice Biennale in 2022, where she was the oldest artist on view.

What marks her work is the Machine Imaginaire, which she started developing in 1959. The Imaginary Machine is a computer without a computer, which means she was already experimenting with algorithms even before she gained access to one. Molnár would work as if she were using a machine, and would draw by hand, on grid paper. She would set very precise guidelines and restrictions that limited the creation of a specific pattern or shape.

In 1968, she could finally get access to a computer at a University research laboratory in Paris, where she taught herself early programming languages. When such cybernetic machines were used for military and scientific purposes, she would feed the screenless and expansive computers with codes, often waiting hours or days for them to respond. She would later transfer the results to paper with a plotter printer. Molnár was very outspoken about the fact that she, not the computers, was making art.

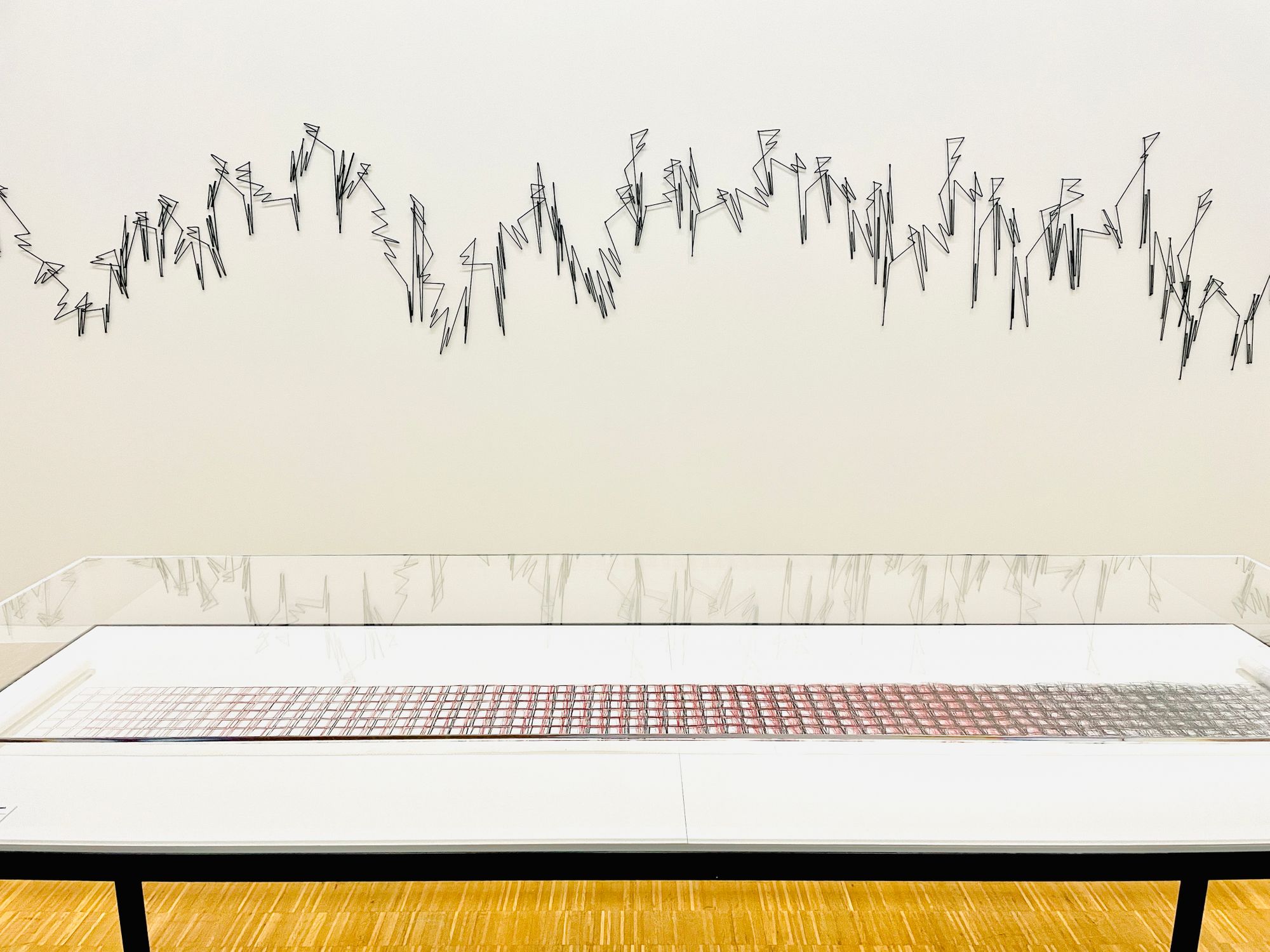

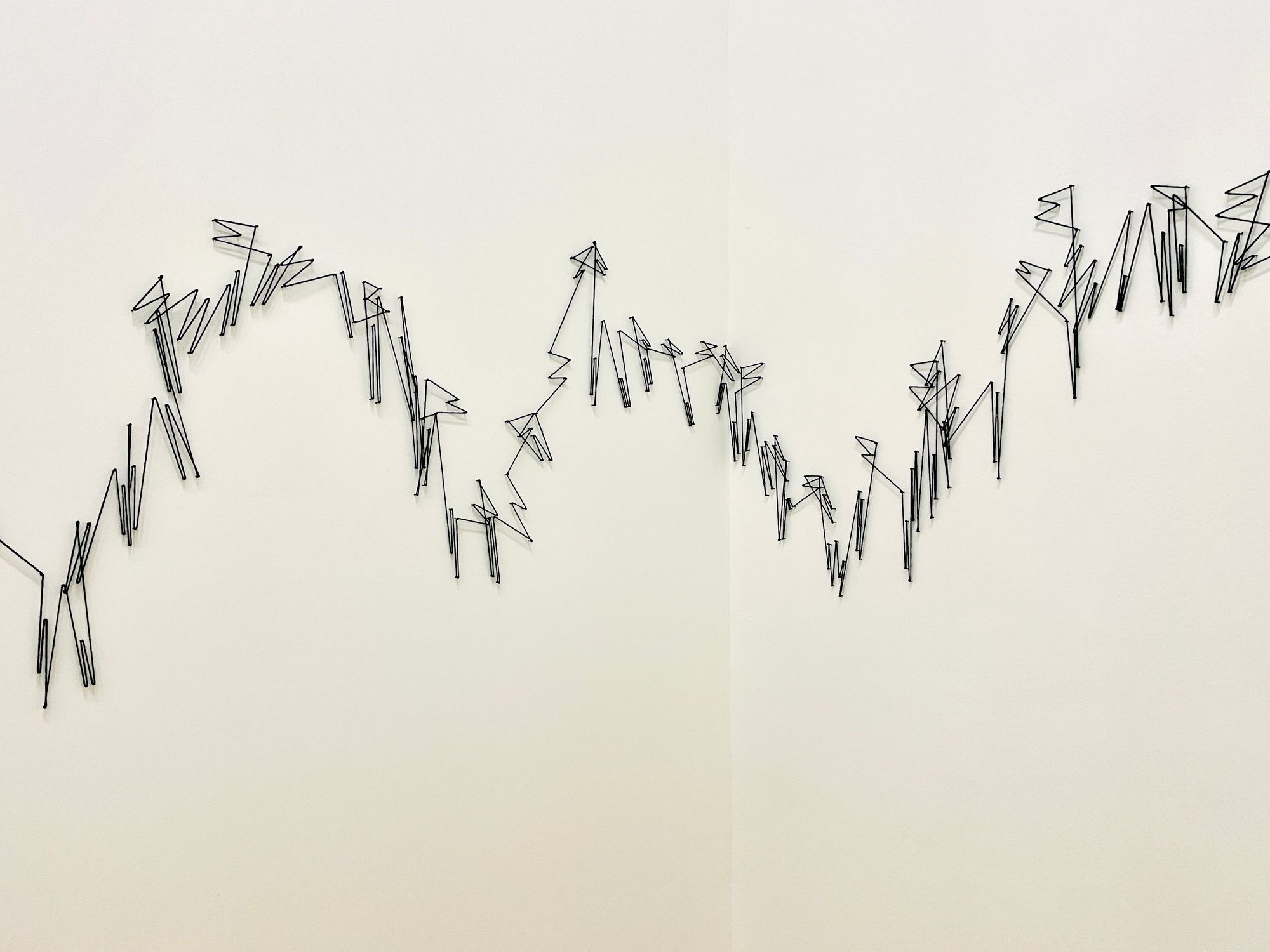

Later in the 1970s, she started using devices with screens, which allowed her to instantly see the results of her codes and adjust them accordingly. She bought her first personal computer in the 80s and developed beautiful works such as OTTWW, on view at the exhibition. Inspired by the poem Ode to the West Wind, by British poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, Molnár created an algorithm that would produce shapes based on a mathematical figure using the letter W. She then used a cotton thread and nails on the wall to recreate the drawings in a visual installation.

Naturally, Molnár experimented with the latest Blockchain technologies towards the end of her life. She made her first NFT, 2% of disorder in cooperation, at the age of 98 in 2022 from the EHPAD retirement home in Paris. Visitors were invited to colour a square of their choice in a grid of 100 white squares. She then painted another square in response, this time in black. Last year, in collaboration with the artist and designer Martin Grasser, she produced a generative art series of more than 500 NFTs for Sotheby's that fetched over $1.2 million in sales.

Ending with a quote by Vincent Baby: "100, minus a few days," he wrote in the text after the artist's death. "Her life and her art were one, as evidenced by her mischievous and wonderful terminological invention from 1977: Moln'art."

Speak to the Eye, by Vera Molnár

February 28th to August 26th, 2024

Centre Pompidou, Paris

References:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/15/arts/vera-molnar-dead.html

https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/magazine/article/ai-nft-vera-molnar-a-step-ahead