by Julia Flamingo

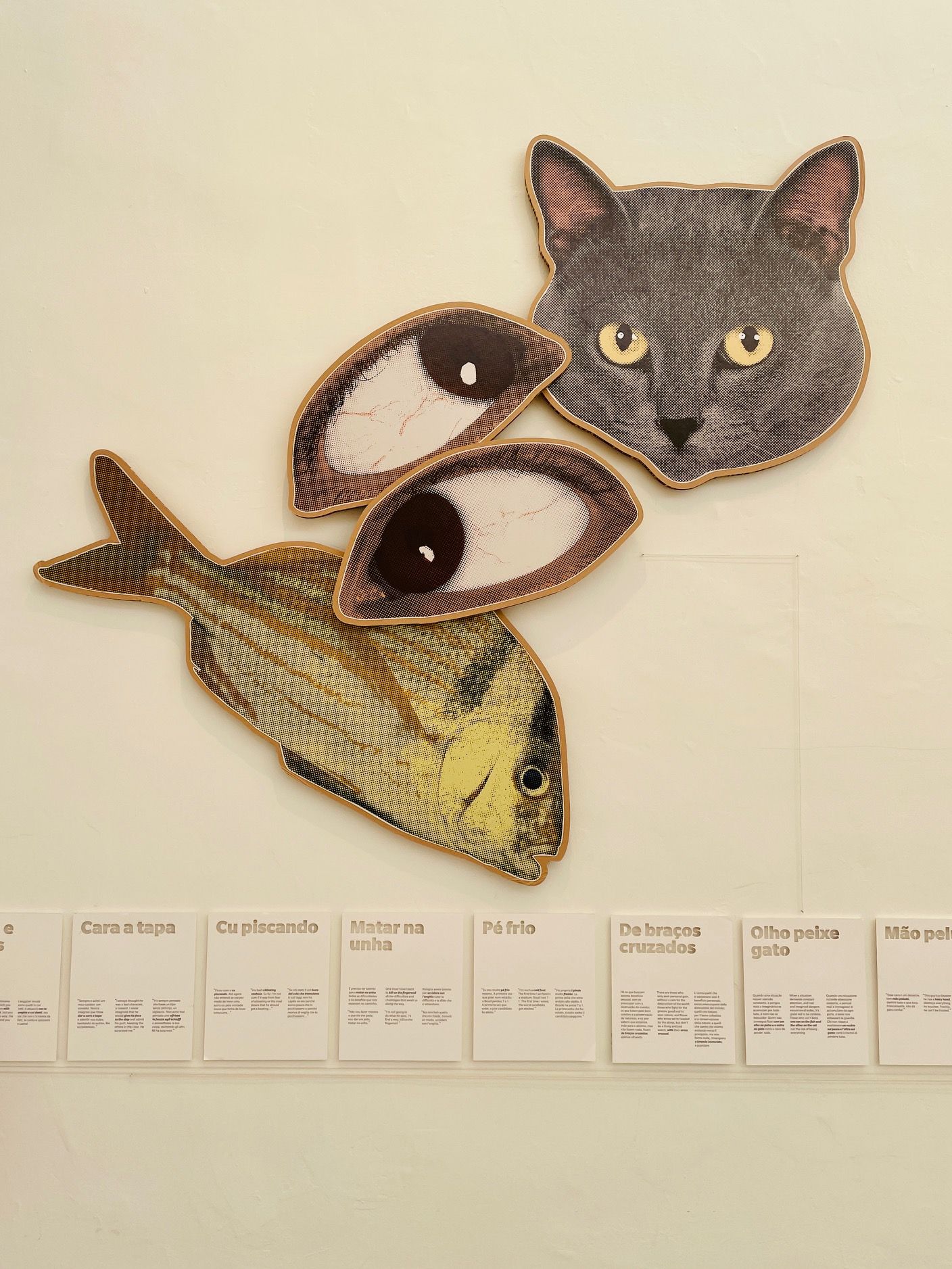

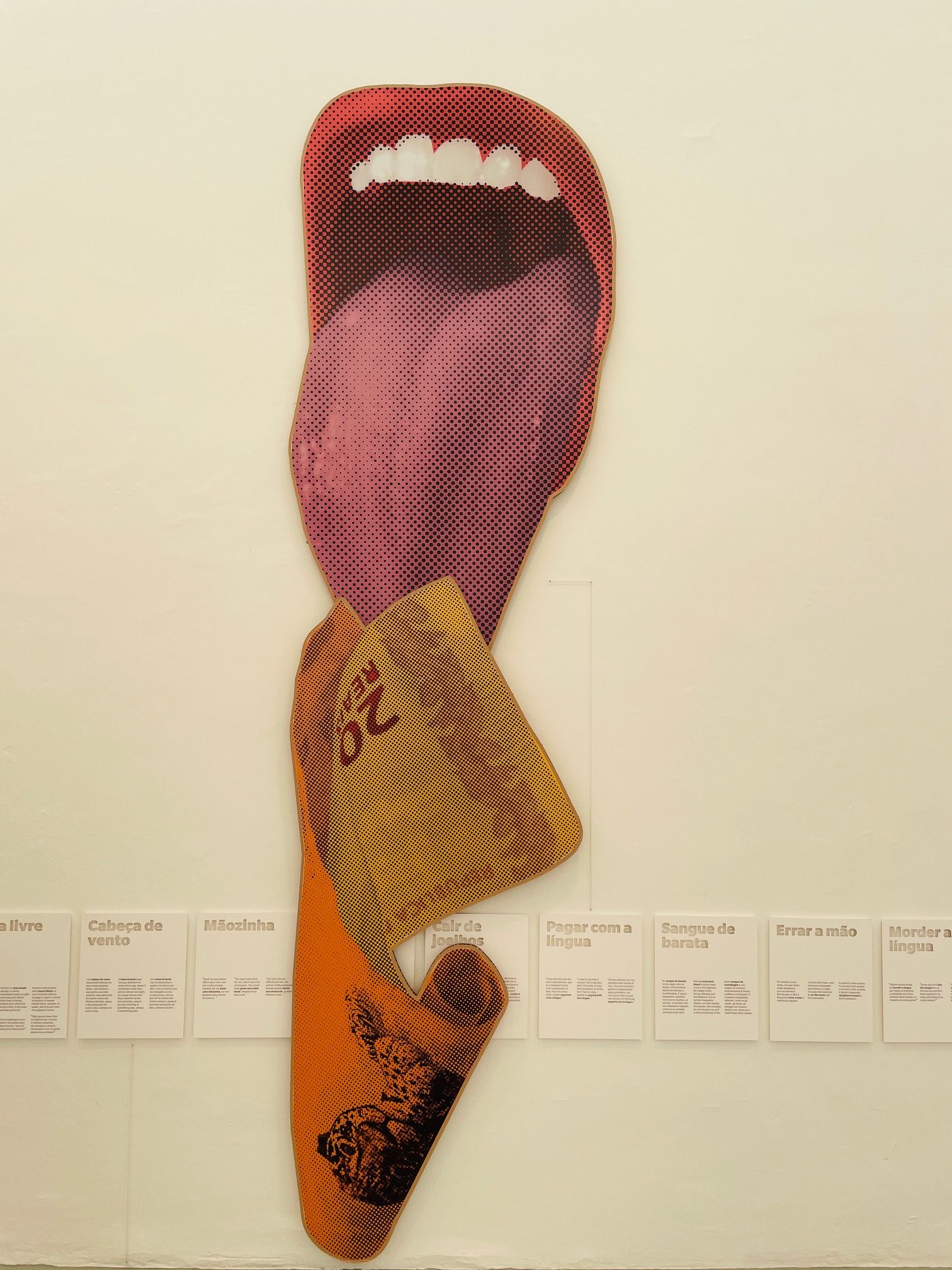

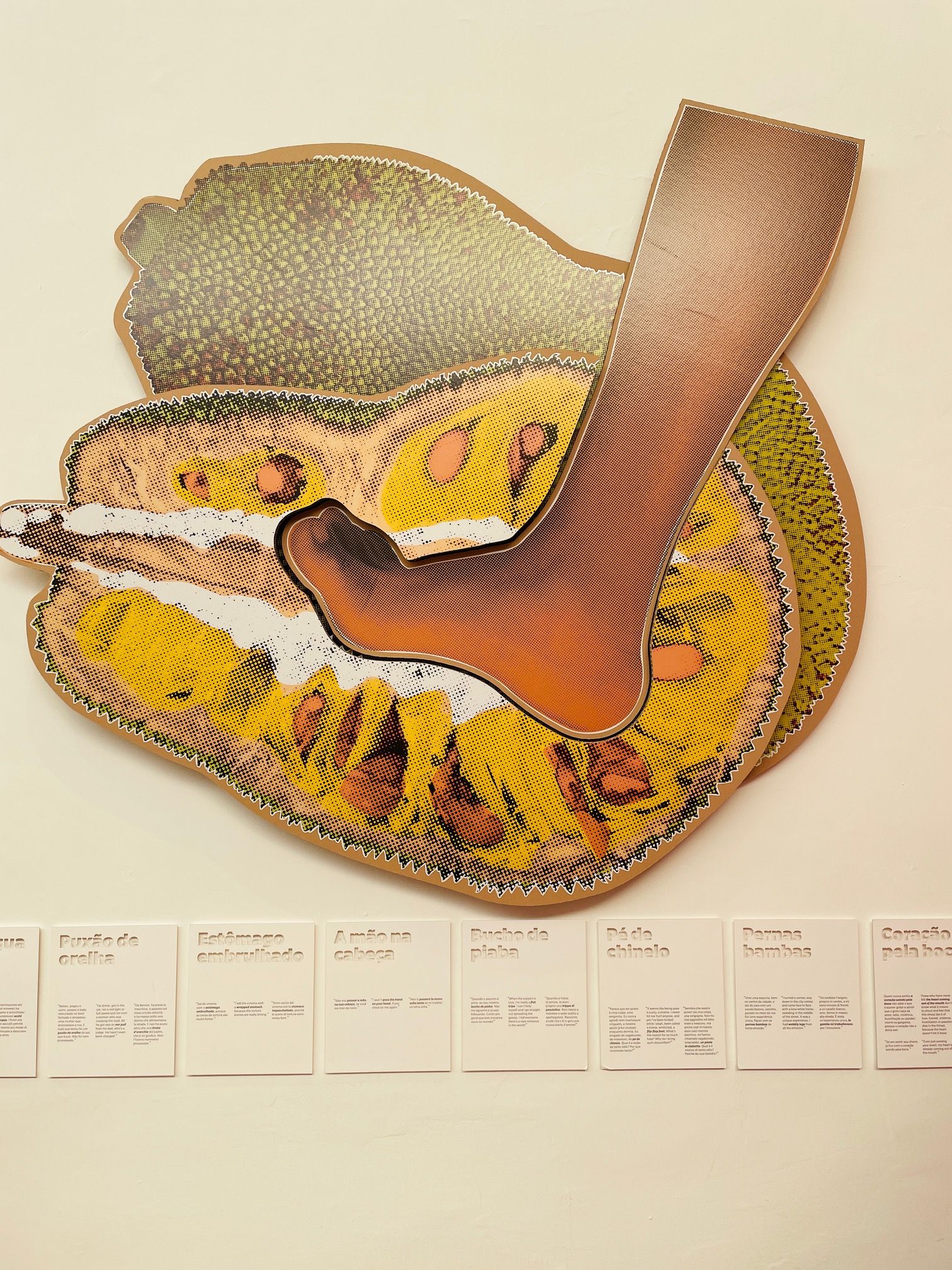

‘In one ear out the other’. Perhaps this idiom doesn’t come directly to one’s mind when strolling through the beautiful boulevards of the venetian Giardini and running into a colossal ear at the entrance of the Brazilian Pavilion during the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale. But it only takes a few minutes after entering the science fair-like organ, to realize the pavilion is taken over by a collection of more than 250 idiomatic expressions all referring to the parts of the body written in plaques, as well as transformed into sculptures with gigantic fingers, hearts and feet.

‘Butterflies in my stomach’ and ‘Bite your tongue’ are some of the expressions which take part in Jonathas de Andrade’s exhibition and work both in Portuguese and in English. However, the majority of the expressions in the show are untranslatable yet an amazing glossary to get in touch with various layers of the Portuguese language, Brazilian culture, context and current struggles. The title of the exhibition itself, Com o coração saindo pela boca [With the Heart Coming Out of the Mouth] stands for a metaphor of the suffocating situation Brazilian people find themselves today, and the difficulties to breath amongst the political, social, health and economical crisis the country has been facing. Today, the collective body of Brazilian people is fragmented, torn apart. The playful and canny works by Jonathas de Andrade echo, reflex and devolve these pressing issues by exploring language, which is itself an expression of the social body. After all, an idiom is only understood if a group of people employ it in their speech.

“As soon as I got invited to be the curator of the pavilion, I started to think which Brazilian artist would comment on the current political situation in Brazil, which was imperative, but still explore other dimensions of art and life. Jonathas is very direct and critical concerning pressing issues in Brazil, at the same time his work is built upon layers of playfulness and poetics. That’s the strength of this exhibition”, says curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti. Born in Naples, the curator and critic has been based in São Paulo since 2000, where he built an outstanding career working as an independent curator and as a member of Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

His name was on everyone’s lips last year, when Viscoti led the curatorial team of the 34th Bienal de São Paulo also formed by Paulo Miyada, Carla Zaccagnini, Francesco Stocchi and Ruth Estévez. It is the second oldest biennial and one of the most important art events in the world - Venice Biennale happened in 1895 for the first time followed by Bienal de São Paulo in 1951. Titled Though It’s Dark, Still I Sing, the 2021 exhibition raised awareness to the darkness and tragedy Brazil and the world were, and still are, facing and acknowledges the power of art to show us new ways to exist and resist. This curatorial concept remains the same at the Brazilian pavilion in Venice. “The most important to me in any curatorial narrative is to build an exhibition with the highest number of layers of understanding as possible. In exhibitions such as Bienal de São Paulo or Venice Biennale, where the audience is extremely diverse, this is at the same time a great challenge and a unique privilege.”

Bunda Mole [Soft Butt], which is the way Brazilians call someone without attitude and chicken-hearted, is illustrated with a very soft puff shaped like a bum where visitors can rest on. Costas Quentes [Hot Back], used for someone who conquers things because of his or her good contacts, is literally a back the size of a human body hung on the wall which people can touch and feel warm. Less amusing and more political, Dedo Podre [Rotten Finger] is a pallid and putrid giant finger pressing the wrong key of an electronic voting machine, which led to the election of the right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro. There are layers of understanding for every person - Brazilians, foreigners, art lovers, children, tourists. One of the best pavilions amongst the 80 national pavilions of the Biennale.

Being a curator at the Venice Biennale is also a tremendous responsibility. It is the only art event in the world which still follows the traditional model of national pavilions. “In Venice, one of our biggest responsibilities as curators is to think about what this outdated model means”, says Visconti. It is inevitable to question things like: how can one artist or a small group of creators represent an entire country? What is nationality and identity today? Another reason why Jonathas de Andrade was the perfect fit for the Brazilian pavilion. In his oeuvre, the 40-year-old artist has always questioned historical processes in his country and the formation of the supposedly 'Brazilian nation'. “Jonathas answered to this issue in a very smart way: he responds to it as a collective. The flash flood of expressions has the role of presenting several voices. Not his, not mine. But the voices of Brazilian people. We all use those expressions.”, says the curator.

During the making of the show, Visconti did not have much information about the curatorial narrative of The Milk of Dreams, title of the main exhibition of the 59th Biennale curated by Italian Cecilia Alemani. Nevertheless, some concepts resonate in both exhibitions: the absurdity of the world we live in, the clear approach to the body and the relationship between body and context, and body and language. “Her exhibition is excellent!”, exclaims Visconti. “Very rich and generous. I enjoyed making connections between her curatorial strategies and ours, such as the time capsules. At the 34th Bienal de São Paulo, we also used statements to punctuate historical narratives and create bridges with the contemporary. It works. And it is beautiful”.