Hosted by Art Curator Grid and Assembly Room NYC in conjunction of The Plus Partnership series

Guest Speakers:

Emily Alesandrini (upon Assembly Room’s invitation)

Gemma Arguello (upon Art Curator Grid’s invitation

Moderator:

Yulia Topchiy (Assembly Room)

This conversation was broadcasted live on Zoom on Wednesday, June 17, 2020

The term “Glass Ceiling” was popular in the 1980s to describe the impediments women faced in economic organizations that prevented them from achieving professional success. It is made of glass because the barrier is invisible: a metaphor for the challenges that keep women from occupying high ranks and being paid accordingly to their work. The term soon began to be applied to professionals in uncountable fields, and later on, other similar concepts took shape: “Bamboo Ceiling” to describe the barriers Asians face in achieving upper-level professional success in the United States, and “Concrete Ceiling” for women of color who face even more obstacles to achieving success in their careers. If once prejudices were hidden, ignored, and therefore perpetuated, nowadays they are a pressing issue all over the world. It is high time not just to break through any kind of biased ceilings, but to build houses where they do not exist.

“Women Curators Discussing Women in the Arts: Rebuilding the House without a Glass Ceiling” was the first webinar of Art Curator Grid’s The Plus series, which took place on June 17. The Curators Conversation was organized in partnership with Assembly Room, which was founded in New York City in 2018, to grow a community of female identified curators across the globe. Recently they have revised their mission: in addition to supporting and empowering independent identified women curators they are also committed to advocate for equality, diversity, and inclusion in the arts and society at large. Following the mission of both Assembly Room and Art Curator Grid, which is to connect and create dialogues through their communities, the webinar gathered sixty curators, art professionals and art lovers from all over the globe to discuss how we can rebuild art spaces and cultural institutions without glass ceilings. We all believe we are collectively responsible to make changes within our communities. Women activists in the cultural realm have been very outspoken and engaged over the last few years demanding changes. But the pressing question remains: which concrete tactics can we come up with to correct imbalances together?

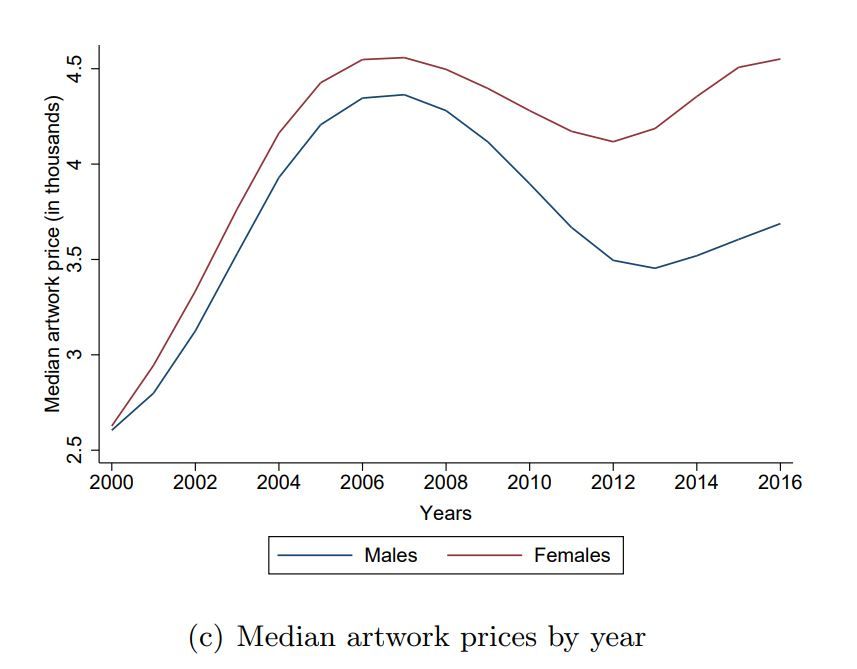

Curator Yulia Topchiy, who alongside Natasha Becker and Paola Gallio founded Assembly Room, was the moderator of the talk and started the conversation with an outstanding introduction. She gathered statistics that show alarming numbers of disparity and inequality in the arts which we share below followed by the related sources:

A recent survey of the permanent collections of 18 prominent U.S. art museums found that the represented artists are 87% male and 85% white ("Diversity of artists in major U.S. museums", Public Library of Science). Only 13.7% of living artists represented by galleries in Europe and North America are women ("The 4 Glass Ceilings: How Women Artists Get Stiffed at Every Stage of Their Careers", artnet News).

In the workplace, women still occupy fewer directorships at museums with budgets over $15 million, holding 30% of art museum director positions (National Endowment for the Arts). Women of color make 15-20% less than white women in the workplace. Three of the most-visited museums in the world, the British Museum (est. 1753), the Louvre (est. 1793), and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (est. 1870) have never had female directors. Women in the arts are found not to experience the “motherhood penalty”—lost or stagnant income after children. But men in the arts do receive an income bump when they become fathers (Artsy). In this pandemic, job losses have hit African-Americans, Hispanics and women hardest (NY Times). [For more facts and numbers check the National Museum for Women in the Arts website]

The first to comment on the statistics was the curator Emily Alesandrini, also a writer working in Philadelphia and New York. Her research concerns contemporary representations of race and gender with a particular focus on issues of displacement, marginalization, and the body in art by women and artists of color. She believes that in spite of contemporary progress in art history it was only over the last 50 years that feminist scholars are working to dismantle the structures that deny women opportunities in the arts and to spotlight the women making great work despite a lack of opportunity. “Art history as a field was founded by white European men 500 years ago, and for 450 years after that, the narrative remained almost entirely homogeneous and glorifying of the male”, she says. So even if the numbers were more equitable we would still have this history on our back of a system built against us.

Gemma Argüello Manresa, the second guest curator to take part in the talk, shared an overview of gender bias within the Mexican art field. She is a researcher, professor and independent curator based in Mexico City and focuses on processual art using participatory and collaborative strategies, but also on electronic art, art and Science, and net-art. Her recent curatorial research topics are migration, feminism, public space criticism and Latin American political art during the 70s. To her, although historically there are many important women artists and feminist artists in Latin America (and in the world), discussions about feminism and the inclusion of women and other groups historically symbolic annihilated (such as LGTB+ communities, Afromexicans, etc.) have only been recently included in the exhibitions.

“Where do you see inequality and unfairness given the education, experience, job market and socio-economic forces that shape our curatorial practice right now?”, asked Yulia. Of course, Emily’s answer was off-putting. She shared her own experience from working in museums and art institutions in Chicago, New Orleans, and New York, and from the stories told by peers working across the U.S. “Young women, young art historians graduate from school with a bachelor’s in Art History (usually with some student loans, I think the average is around 35k). And the job market is very competitive, so we’re told that to become more appealing applicants, we should intern for free for several years and get a master’s degree in Art History or Curatorial Studies (which can cost up to 60 to 100k). Except, even after earning a master’s, those jobs we were told would be easier to get with a higher degree are still painfully competitive. So, after graduating with an MA, and after another year of applying (and interning and working as a waitress to pay your rent), you finally get your dream entry-level job at a small museum or arts organization. You’re elated for two weeks before you realize that you’ve effectively been hired as an administrative assistant and you won’t be asked to contribute to creative projects for another 2 to 4 years”. To wrap up, she stated that this pandemic is a further breakdown of an already broken system. In this scenario, support for one another, mentorships, leadership and collaborations are more important than ever. Being transparent and generous is in the order of the day to thrive within this broken system.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, Gemma has been thinking a lot about the beginning of net-art because it started with a chat as a collaboration between different artists in the 90s. She has joined forces with other peers such as a group of curators and art historians, in order to work on a seminar on depatriarize the archive, and trying to find ways to re-read our art history and women’s artistic production. “It’s difficult because we mostly depend upon the State founding, and with the massive reduction of state’s investment in the art world, we are one of the weakest links”. On the other hand, the pandemic has also forced us to explore the full potential of virtual resources - this webinar is a perfect example of a global collective work that unites people with shared goals and desires. Yulia's final question was provocative, but also a burning issue regarding the discussion on how to build a house without a glass ceiling. “As part of the alternative to the correction of the system, does fighting the male-dominated art world as a curator also mean to only invite women artists to exhibitions?”. To Gemma, women art historians have made us recognize that one of the main problems is based in our approach to the canon and to the categories we use to value artistic production. Therefore, she said, “If we change our curatorial approach we will necessarily invite women”.

On the other hand, Emily answered with a case study of The Studio Museum in Harlem, which advocates for and exhibits artists of the African diaspora. “The work that they do is so good that the art market has stood up and paid attention to black artists. And other museums and cultural institutions have been convinced of the quality of work by black artists, black curators, black museum educators, and are beginning to grant them the equity and attention they always deserved”. As for the women curators, she believes the same has to be done. “I think if we organize, with mission and purpose and quality, we can build alternative spaces that not only serve asa sanctuary for those of us excluded from the art world historically but also have the power to speak back to larger institutions”. Regardless if in Lisbon, where Art Curator Grid is based, in Assembly Room’s New York City or anywhere else in the world, the general and inspiring feeling after we shut down our computers is that we are in a safe space.